While my humble family has not yet been struck by a disaster,...

Tag Archives: Preppers

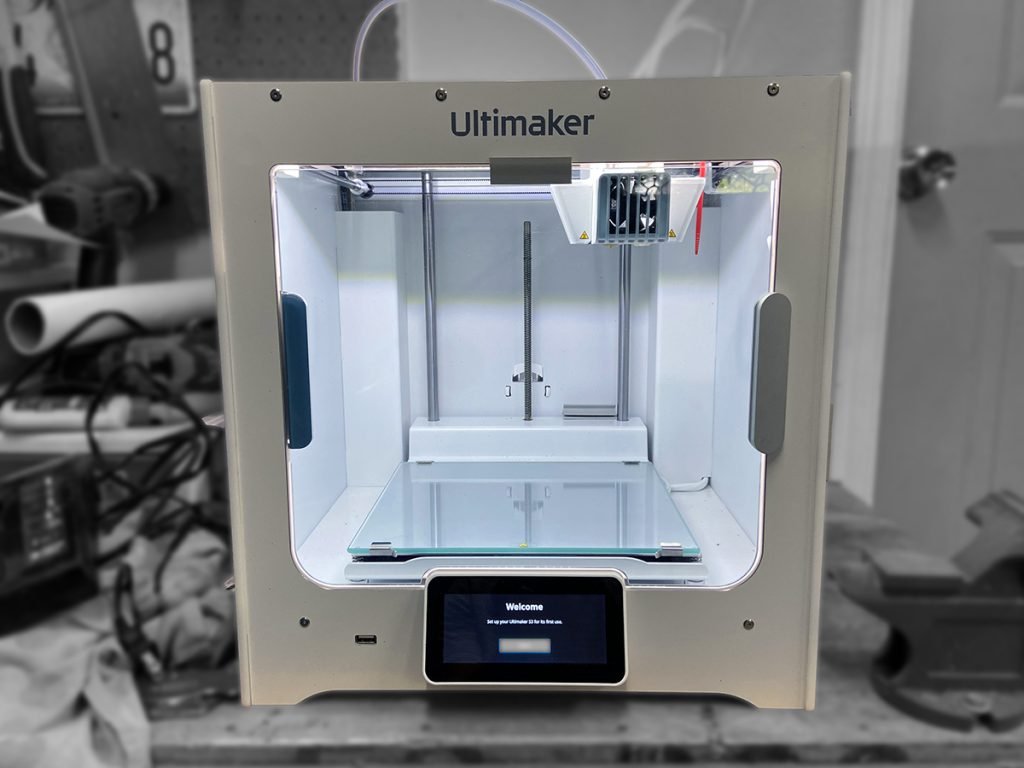

3D Printing for Preppers: The Digital Foundry’s Metallic 3D Printing Filament – 3DPrint.com

28

Dec

Anticipating the expansion of bonded metal printing by severa...

3D Printing for Preppers: Copper 3D Printing Filament – 3DPrint.com

03

Dec

While my humble family has not yet been struck by a disaster,...